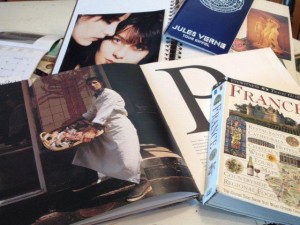

It’s settled: I’m off to France in June for three weeks of Gallic culture! I’ve booked the cutest hotel in Paris for four nights; I’ll be meeting a couple of Parisian girlfriends, but I’m also planning to wander for hours by myself—to take in a couple of museums and the wonderful Les Puces flea market, to buy my new favourite perfume at Galeries Lafayette, and to saunter down cobblestone alleys and the walkways along the Seine River. Maybe I’ll remember some of my French phrases for eavesdropping as I sip vin blanc at a sidewalk café or when ordering bistro feasts. Then I’m off to the South for a visit with my third French girlfriend and her family—including a tour of restaurants, a night in an ancient mas (Provençal farmhouse/mansion), and all the home-grown strawberries I can eat. Superbe!

My friend Dallas shared with me a rivetting article, “Reclaiming Travel,” which appeared last summer in a column in The New York Times. The basic thesis is that today’s tourism (modelled by my upcoming vacation with its focus on rest and restaurants, entertainment, and personal enrichment) is but a faint shadow of real travel (more like a pilgrimage or quest in its cross-cultural, transformational search for meaning). Tourism is largely what we do nowadays; travel is something more rare that changes who we are. The human journey first started, the writers of the piece claim, at our expulsion from the Garden of Eden, when we were condemned to wander—our wandering becoming a wondering about exile and about our true home, with hearts restless for something lost.

Of course, journey is a frequent theme in classic literature; think of Homer’s Odyssey (telling of the Greek hero’s mythic return home after battle) and Dante’s Divine Comedy (a spiritual travel tale tracing the path from the “dark wood” through hell and purgatory to heaven). The meme continues through to stories written today, from Gulliver’s Travels, Innocents Abroad, and Around the World in Eighty Days to Lord of the Rings, A Year in Provence, and Eat, Pray, Love. I could go on, but you get my point.

The motif of travel is omnipresent in the late-Victorian writings of G.K. Chesterton. In Everlasting Man he wrote:

There are two ways of getting home; and one of them is to stay there. The other is to walk round the whole world till we come back to the same place.

Then, encapsulating the nature of journey, in What’s Wrong with the World Chesterton wrote a couple of lines that I used as the first epigram in my own novel:

Man has always lost his way. He has been a tramp ever since Eden; but he always knew, or thought he knew, what he was looking for.

(If you’re interested in the biblical ground for mankind’s wandering and wondering about the road, homecoming, and rest, you might like to read three short literary/biblical studies I posted in April, June, and July of 2012, here.)

My meandering thoughts today have set me on a course of inner contemplation regarding why I love to visit exotic places and what adventure really means to me. My forebears travelled, in the true sense of the word, to make a home in a foreign land—largely for religious freedom. So my history connects travel with spiritual life. Yet here I am, a few generations later, traversing the globe for personal, emotional, and gastronomical satisfaction. Much as I’d love to pretend I might just find an epiphany on French soil, I concede that my trip is more tourism than true travel. I don’t expect great character growth (though I might be surprised); I just hope I properly pronounce merci!

4 Comments