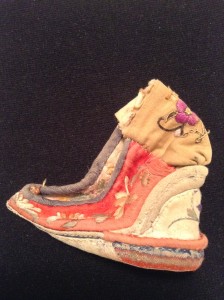

The elegance of this richly embroidered silk slipper, looking like a cute doll’s shoe at three-and-a-half inches in length, belies its hideous history. More than a century old, it was worn by a bound-footed woman in Formosa (Taiwan) and now sits on our bedroom dresser mounted in a black shadow-box frame. The lady would have been fully grown and was possibly of noble birth, the bones of her feet crushed as a child with resulting infection because of a tradition that had been followed for a thousand years—effective in immobilizing women debilitated by pain. This shoe is a symbol of emancipation that came to our house through inheritance from a Canadian Presbyterian missionary, George Leslie Mackay—my husband’s mother’s aunt’s father-in-law. He was the subject of a 2006 televised Canadian documentary, The Black Bearded Barbarian of Taiwan.

Mackay was born in Ontario in 1844 and studied in Toronto, Princeton, and Edinburgh before leaving for the Orient in 1871. He so immersed himself in the culture of his chosen land that he even married a Formosan wife, who herself became an outspoken critic of foot-binding. He served the people for three decades as dentist, anthropologist, educator, evangelist, and author before he died in 1901. Mackay still retains a widespread reputation in that country as the founder of hospitals and schools, and is the subject of a significant Taiwanese opera production.

Why does this matter to me today? I am currently drafting a scene into my novel about a character whose backstory, though set in North America, is all about the sentiments shown by my husband’s shirttail relative. My fictional character faces cultural issues that are new to me, and I need a guide. Now, I didn’t know much about Mackay before we received this silk slipper—so lovely to look at but so horrendous to contemplate. Today our postmodern sensibilities reject the “damage” done to foreign cultures by turn-of-the-century missionaries, who despised practices of paganism that dehumanized people and destroyed the family unit through such brutality as physical mutilation, slavery, and polygamy. I don’t excuse the cultural sins committed by professing Christians who rejected the ethnicity of the ones they came to serve, but I laud the true social reforms made in the name of Christ. I rejoice that there have been and continue to be loving bearers of the Gospel who, although not perfect, devote their lives in going out to all the nations with the welcome news of salvation in Jesus—a salvation that makes a difference in the here and now.

4 Comments